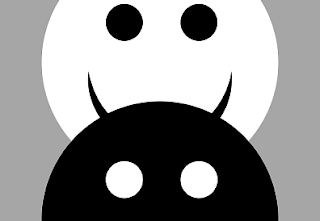

The Dichotomy of Good and Evil in Writing

Most people, if pressed, would describe themselves as “good” yet only one fit that bill. Few would self-classify as “evil”, but there are those who relish in it. Truth is, good and evil are absolutes and there are no such people.

Yet holding a yardstick for benign or benevolent alignment

is a hard habit to break. Why should you bother? I don’t believe you should as

introspection by such tools promotes growth.

There are always going to be examples of people that make

you look like Mother Theresa. Conversely, some may cast you the same circles as

Ted Bundy. But the effort…ahh, that’s the rub.

Self-improvement is based on striving for something more.

Society could use a few more Mother Theresa wannabes. Keep using that

yardstick. Keep trying to be better.

This is assuming we are discussing behavior and intent, of

course. But what if we aren’t talking about outward actions but a character’s

motivation? Writers have to balance that unusual dichotomy of good and evil to

express believable and interesting characterization and plot. Both are needed

for the sake of interest. Think of your favorite writers. Do they do this?

I have read mainstream authors who have mastered the evil

side fairly well and have made a pretty penny doing it. I have also noticed

that a few of these authors struggle with their “good” characters. Without

good, evil is also boring. There must be sincerity in the conflict or it comes

across as trite.

The next time you read, or even watch, an interpretation of

the oldest conflict known to man make sure you examine the spectrum between the

protagonist and antagonist. The best developed villain ever is pointless unless

you have an appropriate foil. Anti-heroes may be in vogue, but I still find

them boring. I mean, who do you root for in villain versus anti-hero, anyway?

There are exceptions to this, of course. Genre and audience,

for example. You don’t want extreme good versus evil in a children’s program. The

antagonist there need not push the envelope. You wouldn’t want a Hannibal

Lector in the Hallmark Mystery of the week, either.

Short stories are also an exception to this rule. The

limitations here are such that characterization is rarely necessary. In horror

anthologies, for instance, emphasis is put on plot and setting rather than

characterization and conflict. It’s the nature of the short story beast.

For the novel, though, characterization is key. Conflict

drives interesting characters. Delving into that contrast between good and evil

helps foster excellent conflict.

Think of your favorite books. Are the protagonist and

antagonist separated by a vast chasm of morality? Could one exist without the

other?

Comments

Post a Comment